I finally have my kitchen back, and now can devote more time to writing and consulting. I am still pushing another project, so my output here will probably be limited. I have taken another look at my bank primer project, and realised that I have too much content — I will need to trim back the theoretical wrangling texts that I previously wrote. With today’s article, I think I have covered most of the content I want to be in the book, although I might stick in some cursory analysis of a few different banks’ balance sheets. For example, I might compare some teeny-tiny American bank versus larger European or Canadian banks as a way of indicating the dispersal of what “banks” are. This article has only been lightly edited.

If the economy was in a stable equilibrium dominated by agents forecasting their cash flows out to infinity, defaults would be a random process – defaults would occur, but without a pattern to them. Default risk would be an insurable risk (i.e., could be managed by actuarial calculations like life insurance). However, the existence and popularity of the term “business cycle” indicates that the flows of commerce are cycle – and defaults follow the business cycle. During an expansion, banks do face a persistent relatively low level of defaults and delinquent loans, which does accord with being a random, insurable risk. The problem is recessions – which see a spike in defaults. Although it is possible for there to be a recession without a default spike (as discussed below), the “interesting” recessions are the ones with default spikes. The “really interesting” recessions are the ones where the banking system itself joins in on the default trend.

American Loan Delinquency Trend

The above figure shows the modern historical experience for loan difficulties for American commercial banks across their entire loan books. The percentages of loans that are delinquent (borrowers not meeting all obligated payments) as well as the percentage of loan losses that are charged off are shown.

The time series are smooth over time (“auto-correlated”), which reflects the fact that they are administered categories, and do not reflect the particular events that lead to default (that would be “lumpier”). If a loan is delinquent, it is going to remain delinquent until either the borrower recovers, or the bank finds a way to resolve the situation (restructuring or forcing a default). Meanwhile, charge-offs to a certain extent reflects banks’ capacity to resolve bad loans. (Although regulators are less happy to allow banks to “extend and pretend” – extend loan maturities to allow borrowers to meet contractual obligations – than was the case historically. Banks that have a large book of “extend and pretend” loans are not going to be trusted counterparties, and one ends up with a crippled banking system populated by “zombie banks.”)

The importance (or not!) of recessions to banking is clear in the figure. The two eras of elevated delinquencies/charge-offs happened with the recessions associated with financial crises – the Savings and Loan debacle of the early 1990s, and the Financial Crisis of 2008. (The Savings and Loan crisis was a drawn-out affair, with high delinquency rates before the recession triggered by the oil price spike caused by the invasion of Kuwait. The use of high interest rates by the Volcker Fed also created persistent credit issues in the real economy.)

The other two recessions in the time depicted do not show credit strains.

The recession in 2001 was concentrated in the technology sector, the rest of the economy was less affected. This recession was also spread across other developed economies via the correlated behaviour of technology companies and investors. There was a credit loss component to the recession – technology and telecommunications bonds did experience large defaults (or credit scares, such as by the incumbent telecom companies in Europe that overbuilt their wireless infrastructure). However, the corporate bond market operated as it was supposed to – the large, concentrated credit risk posed by large technology firms was held by risk asset investors who have balance sheets that can absorb losses better than leveraged entities like banks.

The recession of 2020 (which is barely visible on the figure) showed the opposite pattern than usual – delinquencies fell afterwards. This is certainly not what I expected to happen in real time – I was pessimistic about the economy as felt that the disruptions to activity would lead to credit events. However, the support provided by the government allowed the private sector to improve its financial position. This underlines that the recession 2020 was unusual – it was a contraction created by government policy shutting down private sector activity, and not a freezing of private sector activity that typically reflects credit concerns.

Credit Tightening

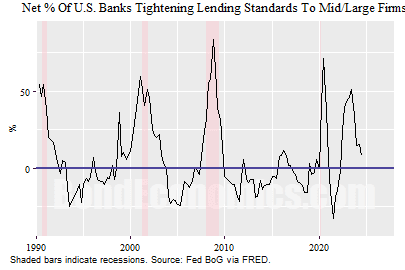

Banks react poorly to the prospect of credit losses, and so their willingness to make loans is also correlated with the business cycle. The figure above shows a series from the Senior Loan Officer Survey in the United States. It shows the net percentage of banks that report that they are tightening credit standards for large and middle market firms. As can be seen, the net percentage has hit 50% in each recession since 1990 (with a spike in mid-2023 not associated with a recession).

Although someone with a cynical attitude towards bankers might expect such tightening to lag the business cycle, the reality is that credit availability is going to be coincident with activity. Lenders stepping away from extending funds to entities burning capital on ill-advised projects is what causes the merry-go-round of industrial capitalism to grind to halt. (That said, regulators are very good at closing the barn door after the horse has already run far enough away that it is incurring roaming charges on its phone.)

Credit Spreads

If lenders are not particularly happy to be extending new loans, pricing on loans is going to be affected. That is, credit spreads will widen. This fits in with the story of Section 4.1, where the fair value of a credit spread is equal to the expected annualised credit loss rate. If there is generalised stress in the credit markets, the implied default loss rate is probably well above most sensible default loss predictions, which can be understood as investors not being risk neutral – they need an extra incentive to take credit risk. (From a less theoretical perspective, technical factors in the market can lead to pricing that appears stupidly cheap from the perspective of most investors – unfortunately, those investors tend to have impaired balance sheets that limits their ability to buy the cheap bonds.)

Concluding Remarks

Under normal circumstances, the business cycle is a credit cycle. A drop in economic activity impairs incomes, leading to credit events. Meanwhile, the fear of credit events causes lenders to get cold feet, leading to the feared drop in activity.

References and Further Reading

When a asset-based lending bubble bursts (mainly real estate), banking systems face crippling losses. One tactic to avoid a recapitalisation of the banking system by the government is regulatory forbearance – allow banks to “extend and pretend.” This is a very popular explanation for the sluggish growth in Japan after its real estate bubble burst. Although I have sympathies for this argument, I think the persistence of slow nominal growth in Japan also reflects the decline of the working age population and the revealed preference for price level stability (as opposed to inflation stability observed in other developed countries). One reference that attempts to identify the effect of zombie banking is: Ahearne, Alan G., and Naoki Shinada. "Zombie firms and economic stagnation in Japan." International economics and economic policy 2 (2005): 363-381.

The pro-cyclical nature of credit is easily demonstrated by browsing time series databases. The Fred economic database of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank is a very useful resource for this. URL: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

The heterodox economic literature emphasises the role of credit in the business cycle (although the mainstream became much more interested in the topic after 2008). Hyman Minsky’s works stand out in this area. I summarised the topic in Chapter 5 of my book Recessions: Volume I.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Posts are manually moderated, with a varying delay. Some disappear.

The comment section here is largely dead. My Substack or Twitter are better places to have a conversation.

Given that this is largely a backup way to reach me, I am going to reject posts that annoy me. Please post lengthy essays elsewhere.