This article is a draft section from my banking manuscript. It fits into a chapter on bank risk management. This article is an introduction to basic bankruptcy procedures, which needs to be understood before worrying about how banks manage the risk of their customers defaulting. This version of the section includes some text about bank resolution procedures that was previously published (but modified here).

Before discussing credit risk management, we need to give some background on credit risk itself. In most cases, credit losses will result from restructurings or bankruptcy procedures. This section gives a high-level discussion of the logic behind bankruptcy procedures. It also includes a discussion of how American bank failures are resolved. (The American banking system produces a high volume of bank failures, and so it has the most developed system for managing the process.)

Bankruptcy Protection

If some entity owes you money and refuses to pay, the standard recourse is to resort to legal action. Non-payment may be the result of a disagreement whether contractual terms were met, and firms can operate normally even though it is in court. However, if a firm is on the brink of insolvency, it may not be able to meet its contractual payments. In theory, every entity owed money could rush to court and then attempt to seize assets to pay off their debts. Such a rush of litigation and judgements would destroy the viability of the firm and would result in unfair outcomes – the first parties to get to court would get paid off in full, while the later parties would likely get nothing.

The inadequacy of relying on adjudicating contracts one at a time resulted in countries enacting statutes regulating bankruptcies. Individuals with relatively small debts operate under simplified rules, while large cases end up in court. For business bankruptcies, the objective is to find an outcome that best serves all parties to the bankruptcy: employees (and management), customers, keeping the firm operating, as well as the creditors. Different countries weigh the differing claims differently, and the legal procedures vary. Bankruptcy judges have considerable power to determine the outcomes, which forces the parties to be flexible in their negotiations since they cannot guarantee that the judge will rule in their favour based on the laws.

Firms that fear insolvency go to a bankruptcy court seeking bankruptcy protection. This puts the firm in a legal status (of which there are typically a few variants) that protect the firm from any attempts by creditors to seize assets. The bankruptcy procedure then involves identifying all claimants, and then negotiating a solution.

There are two broad ways of ending a business bankruptcy. Either the firm restructures its debts (contracts are renegotiated for ones that are less costly for the debtor) or the firm is liquidated. In a liquidation, all assets are auctioned off, and the proceeds are used to pay creditors in order of priority. For industrial firms, the recovery on liquidation is typically lower than a restructuring. For firms that borrowed against financial instruments or real estate, recoveries can be higher.

Liquidation Priority

If a bankrupt firm is liquidated, all its assets are sold, often in auctions or similar methods. This might take considerable time, but for our purposes here, assume that it happens all at once. For now, assume that no assets have been used as collateral for loans.

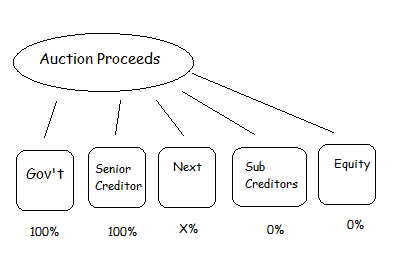

The diagram above shows what happens next. All creditors are organised into “classes” based on bankruptcy law. Each credit claim’s dollar amount acts as “share” within the class, and the class has a total amount due to it which the sum of all the claims in that class.

The payment proceeds are then paid out to those classes, in order. Government taxes get paid first (of course). After that, payments are made to classes in order, until the funds raised in auction run out. In the diagram, the “Senior Creditor” gets paid out in full (100%). The “Next” class uses up the auction proceeds, but with a shortfall. Every claim in the class is paid out the same percentage (“X%”) of the claim amount. All the classes below that class (theoretically) get nothing. (It is possible that subordinated groups will end up with something after negotiations, since they have an incentive to drag out the costly legal process.)

Banks generally ensure that their loans are senior to all the creditors, including unsecured bonds. The original owners of the firm (“Equity”) is always at the bottom of the priority list and got 0% in this example.

The possibility of a liquidation determines the bargaining strength of parties in bankruptcy negotiations. Since the overall recovery under a restructuring is typically higher than under a liquidation (and the bankruptcy process is expensive), junior creditors still have an ability to extract some concessions in order to allow a restructuring to take place.

American Bank Resolution Procedures

Bank bankruptcy is more complicated, and so tends to be treated differently than the failure of industrial firms. Banking regulations differ by country, and the same is true for how failing banks are resolved. This text will just use the American system as an example, on the basis that American bank failures are more common than in other developed countries. The cost of having a fragmented banking system is that small banks are more fragile and cannot invest heavily in risk management.

The key difference between the generic firm bankruptcy process and bank resolution in the United States is that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) administers the bankruptcy under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act. Different classes of creditors make claims, but do not negotiate a resolution — it is imposed by the FDIC. (The technical detail in this section relies on an article by Robert R. Bliss and George G. Kaufman listed in the references section.)

The Act creates two classes of super-senior creditors: insured deposits, and uninsured deposits. At the time of writing, the insurance limit on deposit accounts was $250,000, which meant that a depositor with a $1 million deposit would have two claims: a $250,000 insured deposit, and a $750,000 uninsured deposit.

The usual resolution procedure is that FDIC agents swoop in on Friday after the close of business, shutter the bank, and some new bank (possibly operated by the FDIC, or another bank assuming the failed bank) is open for business on Monday. (The Silicon Valley Bank failure on March 10, 2023 was unusual in that some geniuses organised a bank run over social media, forcing the FDIC to shut down the bank during business hours.) The objective is to minimise the disruption for depositors.

The FDIC allows insured depositors to withdraw cash from the new bank. This creates a drain on FDIC funds, which is matched by the FDIC assuming (subrogating) the original claim. (Subrogating is a cool word and needs to be used more.) This means that the outflow does not affect the waterfall of claims on the bank assets, just moves the claim from the original depositor to the FDIC.

For uninsured deposits, they normally get a claim certificate that is a negotiable instrument. That is, they can sell the claim at a discount to raise cash. In the Silicon Valley Bank bankruptcy, the FDIC waived this condition and offered a full guarantee on uninsured deposits (which I will discuss below), so the two classes of deposits ended up merged.

Since the depositors (and subrogated FDIC) have priority, they get paid before all other classes of creditors. This means that the FDIC only takes a financial loss on a bank failure if the losses from the failed bank blow through every other layer of the bank’s capital structure — equity, preferred equity, and all the various seniorities of bonds. (The FDIC will also incur administrative costs during the workout.) Since regulators are supposed to ensure that losses are less than the equity of the bank — never mind the other layers of capital – that requires a somewhat drastic regulatory failure for such losses to show up. Deposits are supposed to be safe, and all the other layers of the capital structure are sacrificed to make them so.

The Silicon Valley Bank

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB hereafter) was an unusual institution and acts a counterexample to what I argue is standard risk management practices at large banks.

Silicon Valley Bank started as a small bank, but it grew along side the venture capital industry in Silicon Valley. Its parent company (Silicon Valley Bank Financial Group) amassed $212 billion in assets ahead of the group’s failure. Despite its size, it did not face the same stringent regulation that global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) face. (The Federal Reserve published a summary of its evolution as well as the causes of the failure that is cited below.)

The underlying problems with SVB where concentration and duration risk. The bank relied on large deposits coming from a single local industry, and those industry members were in constant contact with each other. This created concentration risk for its funding. The bank needed an extremely large liquidity portfolio to manage that liquidity risk, but SVB management effectively rolled the dice on interest rates and had a large hold-to-maturity bond portfolio. The market value of that portfolio was shattered by the bond bear market, and the spectre of insolvency hung over the bank. Although it limped along for awhile, it was finally put out of business by the run of large depositors. (The article by Cipriani, Eisenbach, and Kovner in the references examined payments system data and found that the outflows were concentrated among large depositors, retail depositor behaviour did not appear unusual.)

The FDIC was criticised for bailing out the uninsured depositors, but this was justifiable on systemic risk grounds. There was widespread fearmongering about other banks failing due to losses on their bond portfolios, and the bailout was presumably intended to forestall this by demonstrating to depositors that they would be made whole.

Concluding Remarks

With the background information on bankruptcy procedures out of the way, we can next look at how banks manage their credit risk.

References and Further Reading

An example of a government agency that manages bankruptcy is The Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy in Canada. They manage the procedures for handling small bankruptcy cases. URL: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/office-superintendent-bankruptcy/en/bankruptcy-and-insolvency-glance/bankruptcy-and-insolvency-glance

U.S. Corporate and Bank Insolvency Regimes: An Economic Comparison and Evaluation” by Robert R. Bliss and George G. Kaufman URL: https://www.chicagofed.org/-/media/publications/working-papers/2006/wp2006-01-pdf.pdf

“Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank - April 2023” Federal Reserve. URL: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2023-April-SVB-Evolution-of-Silicon-Valley-Bank.htm

Cipriani, Marco, Thomas M. Eisenbach, and Anna Kovner. 2024. “Tracing Bank Runs in Real Time.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 1104, May. https://doi.org/10.59576/sr.1104

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Posts are manually moderated, with a varying delay. Some disappear.

The comment section here is largely dead. My Substack or Twitter are better places to have a conversation.

Given that this is largely a backup way to reach me, I am going to reject posts that annoy me. Please post lengthy essays elsewhere.