I will point the reader who is interested in those articles to Klein’s piece on the basis that I have not yet read those papers. They are working within the mainstream tradition, and in my view. that tradition took a wrong turn a very long time ago.

My view is straightforward.

Modulo some technical issues, once interest rates were deregulated, bond yields track rate expectations. When interest rates were regulated, they were typically where regulators wanted them. Those regulations were in place up until the 1970s in most jurisdictions, and they survived into the 1980s in some cases. (This means that any academic article that compares regulated to nonregulated bond yields is comparing apples to oranges. By implication, the available time period wipes out most of the interesting part of the history.)

Central bankers are herd animals. This can be explained by “great minds think alike/fools follow ruts,” depending upon one’s personal views. Policy rate spreads were watched closely, and so the interest rate data is not exactly independent across currencies. Japan was one of the few developed countries that had rates that were “outliers” (until everybody else converged down).

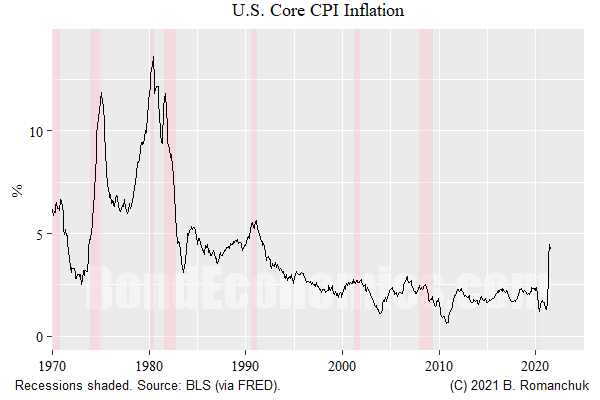

Central bankers set rates as a spread to inflation, and inflation rates went up across the developed countries in the 1970s, peaked in the early 1980s, and then went down. Once again, Japan was the closest to an exception to that pattern.

I am in the process of getting my international inflation data ported to my database, and I am unfortunately stuck with just the U.S. core inflation chart (above). The reader will have to take my word on the experience in other countries being similar.

Based on the above logic, rates went up with inflation, then went down. Inflation rates fell faster, while interest rates lagged behind in a somewhat adaptive expectations fashion.

Anything that Breaks Trend in 1980 Fits This

The issue with trying to “explain” interest rates using some other factors is that anything that breaks trend in early 1980s works. Given that there was a conservative counter-revolution that started in the early 1980s, there are plenty of candidates.

This explains why I do not see inequality as being the cause. Instead, rising inequality is an outcome from changes in policy, and those same changes in policy probably helped the cause of disinflation.

Demographics?

The demographic story has two angles.

An ageing population has caused inflation rates to be lower.

An ageing (and wealthier, which ties into inequality) creates a demand for bonds, driving down rates.

The link between ageing and inflation is once again complicated by other factors. It is clear that an ageing population that developed an aversion to inflation would favour anti-inflation policies. As such, I can see a link — at least for the current generation, but how durable this is remains to be seen.

However, any belief that inflation is impossible because of demographics is likely as to be as durable as Larry Summers’ view on “secular stagnation”: something is a secular, unstoppable force of nature until it ain’t.

The past year shows that inflation can be generated by blowing past an impaired supply side. I have always been skeptical about rising inflation calls, but I never viewed generating inflation as impossible.

If we looked at the dependency ratio instead of age, it is just as easy to say that a secular inflation is coming. (The dependency ratio is the ratio of dependants to the working age population.) When the baby boomers were still in school, the dependency ratio was high, since school kids are dependants. They then entered the workforce, and inflation tamed down. Now when they head off into retirement, they are once again dependant upon others to provide goods and services.

Neutral Rate

The papers that Klein discussed appear to be more advanced than just looking at levels of interest rates, instead, they are looking at the evolution of the neutral rate. This is exactly what we would expect from mainstream economists.

The issue is straightforward.

If you believe the neutral rate exists and works like neoclassical economists believe, it fell since the early 1980s.

If you do not believe the neoclassical story about the neutral rate, the measured “neutral rate” will just track the actual policy rate without doing much of anything. It fell because central bankers kept cutting rates, which had no effect on the economy because we don’t believe in the neutral rate.

This is a question of theology, not science.

I Don’t Buy the Bond Demand Story Either

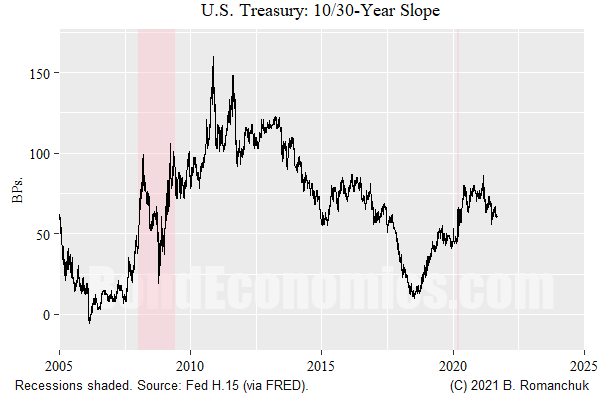

One could try to argue that bond yields are being suppressed relative to the policy rate because of demand. Although that is certainly possible, I do not see that much evidence of it.

People who want to liability match retirement cash flows need duration, and lots of it. They want to buy long-dated paper, like 30-year bonds. If we look at the 30-year U.S. Treasury, it is bouncing along at a spread of roughly 50 basis points over the 10-year. This is not like what we saw in the U.K. gilt market, where asset managers were herded into 30-years because of liability matching.

Academics love producing papers “proving” that bond yields are distorted. They are just doing their jobs (producing paper that nobody reads). However, they are ignoring that other people do their jobs as well.

Bond managers want to make money, and so they want to price bonds efficiently.

Governmental debt managers’ jobs involves talking to investors to see where demand is for paper.

Most issuance is short. If demand picks up for duration, debt managers can easily accommodate this.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete