(This is a rather lengthy unedited excerpt from the manuscript of my MMT primer. It has references to other sections of the manuscript.)

The modern version of the theory relied up the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment – NAIRU – although if one digs into academic history, there are a few related measures with slightly different definitions. Since I want to focus on MMT – and avoid going too far into the swamp of critiques of neoclassical macro – I want to underline this section is offering a simplified version of the evolution of the concept. Interested readers are pointed to the text Full Employment Abandoned: Shifting Sands and Policy Failures by William Mitchell and Joan Muysken. From my perspective, the historical development of these concepts might be of interest of historians of economic thought, but from an empirical perspective, any measure like NAIRU is found to be of no use in understanding the economy. Within the physical sciences and engineering (which I briefly taught), we do not waste students’ time going through the history of failed concepts.

Really Short History of NAIRU

The history behind NAIRU is long, and to do it properly, one would need to watch the full evolution of economic theory. Rather than attempt to do that, I am going to focus on the political economy aspects. I will caution the reader that it is simplistic, but my argument is that you need to get the big picture view before being bogged down in who said what.If we look back to the pre-Keynesian era – normally called classical economics – the working assumption was that all markets moved to equilibrium courtesy of the laws of supply and demand. The story was that unemployment was essentially a natural outcome of market processes, and there was little to be done about it. If the economy is perturbed by some disturbance (a depression or recession), it will move on its own back to the level where all workers who want to work at the prevailing wage are employed. (Note that business cycle analysis as well developed as it is now, and it is not clear how seriously held this view was. This may have just been pro-market propaganda produced for the masses.)

John Maynard Keynes created the field of macroeconomics when he launched his theoretical research programme into the business cycle. The politically-charged insight of this programme was that unemployment rates can stagnate at a level above what would be seen as “efficient.” A such, governments had an imperative to drive down the unemployment rate – the Full Employment framework described in Section 2.2.

Free market-oriented politicians and economists were not happy with the social programmes aimed to reduce unemployment, and eventually launched a counterattack. The main theoretical concept advanced was the natural rate of unemployment, proposed by Milton Friedman. The idea is straightforward: if the unemployment rate falls below the natural rate, the economy will experience accelerating inflation. Although Friedman cautioned that the word “natural” was derived from usage elsewhere in economics, it was effectively mis-interpreted as being a “law of nature” and immutable. (Friedman did argue that the rate depended on other factors.)

(From the perspective of MMT, this episode is a useful example of the concept of framing in economics. Why call it the “natural rate” if it is not a law of nature? One could easily assume that this was a deliberate attempt to mislead the broad public.)

The original formulation of the natural rate of unemployment failed miserably as an empirical concept. Nevertheless, new variants of the concept appeared. In North America, the concept of NAIRU was the most popular replacement. (European theory diverged slightly, following the path set in the text Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market, by Layard, Nickell, and Jackman. I will stick to the consensus North American version of the theory for simplicity.)

NAIRU: the U.S. Experience

If one looks at the historical debates about NAIRU (and its relations), it is easy to drown in details. However, if we focus on the post-1990 period, it becomes much easier to discuss. The issue is straightforward: the concept failed empirically, and it is fairly clear that there is no easy way to save it. This was not the case in earlier decades: new models were proposed that at least fit recent historical data.For reasons of simplicity, I will look at a single measure of NAIRU: the long-term NAIRU produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). It is extremely likely that one could find a different measure that performs slightly better, but that is clearing an extremely low bar.

The figure above shows the movements of NAIRU and the U-3 (headline) unemployment rate. The top panel shows the levels since 1990, while the bottom shows the difference – NAIRU minus the unemployment rate. (It seems preferable to subtract NAIRU from the unemployment rate, but I am reversing it for reasons to be discussed below.) I am labelling this difference the “employment gap” – as an analogy to the output gap – but I warn that this may not be standard terminology. I cut off the charts in January 2020 to avoid the jump in 2020, which obscures movements in earlier decades.

As can be seen, the unemployment rate spikes higher during recessions, and then grinds steadily lower during the following expansion. (The 2020 experience is likely to be erratic due to the nature of the slowdown. At the time of writing, only a few post-pandemic datapoints are available.) The unemployment rate slices through the relatively slow-moving NAIRU.

Keep in mind that there are many ways in which one could calculate a NAIRU estimate. However, the premise is that it is a slow-moving variable, similar to the CBO measure shown. If we replaced the CBO NAIRU estimate with any variable that meets that criterion, all that would happen is that the unemployment gap measure just shift up or down by a certain amount, but the qualitative picture would be the same. That is, the unemployment rate drives below the new series during the expansion, and then shoots above it during the recession. (If the measure was always above or always below the observed unemployment rate, something is obviously wrong.)

Just a simple visual analysis of this chart largely puts to rest an ancient theoretical debate: does the unemployment rate “naturally” converge to NAIRU? Given that it typically took around half a decade to close the negative employment gap after recessions, the reversion speed is too slow to be of any interest.

NAIRU and Inflation

Instead, modern theories of the NAIRU (and its relations) suggest that the employment gap ought to be a determining factor for inflation. The initial problem is that “inflation” is somewhat vague: in this context, one could either look at wage inflation, or the rise of consumer prices (e.g., the CPI). (Yet another alternative is the GDP deflator, but the GDP deflator has some unusual properties that I do not want to deal with.)If one delves into the economic literature (including Full Employment Abandoned), whether one uses consumer price inflation or wage inflation matters if one looks at the historical development of models (who gets credit for what). Since these models have obvious weaknesses, I am not too concerned about these distinctions. For completeness, I will show both variants.

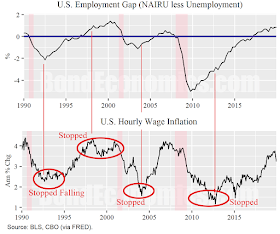

The chart above shows the experience of the employment gap and the changes in average hourly earnings in the United States since 1990. The top panel shows the employment gap (NAIRU minus the unemployment rate), and the bottom panel shows the annual change in average hourly earnings.

One initial reaction is that the two series are correlated (the two series move up and down together). This is exactly what one would expect if wage inflation is correlated with the business cycle – which is a prediction of most plausible economic models.

However, this is not enough – we need to see whether inflation is accelerating (since accelerating is the “A” in NAIRU). As we can see, this is not happening. Wage inflation bottoms after a recession, but it does not keep falling. If we look at the three circled episodes after recessions, wage inflation stopped falling when the employment gap was negative – which means that it did not keep falling, even though the employment gap was still negative for a few years. As for a positive acceleration, the one clean episode where the employment gap was clearly positive (in the 1990s), we see that wage inflation stopped accelerating years before the recession (and the employment gap was positive). (The employment gap did not get very positive in the latter two expansions, so the picture is not particularly clear.)

The figure above repeats the analysis with core consumer price inflation – excluding food and energy. (Although the use of core inflation distresses some people, the difference between headline and core is largely the result of gasoline prices. Energy prices are important, but oil price spikes cannot be exclusively pinned on U.S. domestic policy settings in the post-1990s period.

If we put aside the period of relatively high inflation in the early 1990s, we see that core CPI inflation stuck near its period average of 2.4% - with dips that occurred after the recessions that started in 2001 and 2008. Core CPI inflation was correlated with the employment gap – an unsurprising outcome given they are both pro-cyclical – but given the scale on the graph, we see that “acceleration” in inflation is negligible.

With some ingenuity, one could attempt to explain away the lack of acceleration by appealing to other factors that coincidentally always managed to cancel out the acceleration predicted by the NAIRU concept. I will return to that argument in the technical appendix.

The Policy Debates

The three expansions after 1990 featured the same debate: the unemployment rate is about to drop below NAIRU, so should the Federal Reserve hike rates to counter-act the risks of rising inflation? The lack of accelerating inflation was typically seen as the result of flawed estimates of NAIRU; if we improved the methodology, NAIRU was lower than expected. Pavlina R. Tcherneva discusses the “search for NAIRU” in Chapter 2 of The Case for a Job Guarantee.This argument that any particular NAIRU estimate (like the one produced by the CBO) is flawed and could be replaced by a better one is entirely reasonable. If we assume that economics is a science, we need to adapt our theories to observed data. However, I have some deep reservations with this view. Given the complexity of the topic, I have deferred this discussion to a technical appendix at the end of this section.

Rather than debate estimation methodologies, there is a much simpler alternative: NAIRU does not exist. The title of Chapter 4 of Full Employment Abandoned is “The troublesome NAIRU: the hoax that undermined full employment” offers a hint as to what the authors’ views on the matter are.

From my experience, when one argues that NAIRU does not exist, one is hit with a wall of objections. The objections that I have seen were not particularly strong, as my feeling is that the people raising the objection are conflating “NAIRU does not exist” with “there is no relationship between unemployment and inflation.”

I will start off stating what I see as a minimal version of the statement “NAIRU does not exist.” The statements are theoretically weak (assume very little) but are easily understood. However, this is how I interpret MMT, and thus need to be taken as a grain of salt. I will then discuss some of the comments from Full Employment Abandoned, which is an authoritative source.

I argue that the following terms are safe observations to make about the business cycle.

- Inflation (however defined) is positively correlated with the business cycle: it tends to rise during an expansion.

- The unemployment rate is negatively correlated with the business cycle. (This seems almost to hold by definition, but people enter/leave the workforce.)

- The two previous statements imply that should expect to see a local relationship between unemployment rate changes and the inflation rate. This implies that we can typically fit a NAIRU-style relationship to a small segment of historical data.

- The unemployment rate and annual (core) inflation both feature trending behaviour: the level in the current period is relatively close to historical values. (There is considerable noise in annualised inflation rates on a month-to-month basis, but that noise tends to cancel out, so that the annual average follows a trend.)

- This trending behaviour means that the local models in (3) can be spliced together in back history, but one would expect that predictions based on such splices will tend to break down.

The implication of this logic is straightforward. It is a mistake to look at historical data and argue that if the unemployment rate drops below some arbitrary level in future years, inflation will accelerate. That was the mistake that policymakers and market participants kept making over the 1990-2020 period. (Will they do it after 2020? That may depend upon the theoretical success of MMT.)

Mitchell and Muysken phrase the idea differently.

We have demonstrated (in Section 4.2) that contrary to theoretical claims of the natural rate theorists, non-structural variables have an impact on the NAIRU, which means that aggregate demand variations can alter the steady-state unemployment rate. This insight, alone, undermines the concept of natural unemployment, or NAIRU, which is driven by the notion that only structural measures can be taken if the government wants to reduce the current steady-state unemployment rate. As a consequence it is little wonder that the concept of equilibrium unemployment lost its original structural meaning and becomes indistinguishable in dynamics from the actual unemployment rate. [Section 4.2, page 116]These statements are somewhat more complex than saying NAIRU does not exist, rather it is saying that if it existed, it does not behave the way that “natural rate theorists” suppose. Fans of arcane theoretical disputes will probably prefer this phrasing, but my argument is that the plain English interpretation of the phrase “NAIRU does not exist” covers this more complex theoretical position.

The jargon about “structural” and “non-structural” might be unfamiliar. To interpret, “structural” factors are institutional barriers that allegedly cause people to remain unemployed. From the neoliberal perspective, these are mainly the result of social programmes that give incomes to the unemployed. Non-structural factors are those related to the business cycle. I now will turn to one such factor that is highlighted by Mitchell and Muysken: hysteresis.

Hysteresis

Bill Mitchell’s work in the 1980s emphasised the concept of hysteresis, although the idea has a longer history. (Full Employment Abandoned provides a 1972 quotation from Edmund Phelps that used the term in this context. Hysteresis is a term used in physics and is typically described as “path dependence.”In the case of unemployment, the definition is as follows. Firstly, we need to assume that there we can define something resembling NAIRU so that the employment gap offers useful predictions about inflation. If hysteresis is present, this measure is affected by the historical trajectory of unemployment. More specifically, if the rate of unemployment was high, the estimated “NAIRU” will rise.

Although this might sound like the case without hysteresis, this has radically different policy implications. By driving the unemployment rate lower, the value of “NAIRU” is lower. It implies that there can be a trade-off between unemployment and inflation, and that policies that create employment are optimal – since they are associated with lower steady state unemployment. Meanwhile, this help explain the lack of inflation acceleration discussed earlier. If “NAIRU” is just tracking the unemployment rate (similar to taking a moving average), inflation will not move very much.

There are several ways in which hysteresis can arise – the literature surveyed in Full Employment Abandoned gives a number of mechanisms. Although this of interest to academics, from a practical perspective, it means that “NAIRU with hysteresis” does not behave the way the consensus assumes (e.g., the only way to lower it is through “structural reforms”). From a forecasting perspective, the concept is largely useless. Since the reality is so far away from beliefs about NAIRU, I would argue that the simplest description is that “NAIRU does not exist.”

From the perspective of MMT, the key conclusion to draw from this line of argument is that it makes little sense to keep people unemployed in order to stabilise the price level. This will be expanded upon in the discussion of the Job Guarantee in Chapter 3.

Technical Appendix: Falsifiability?

Given that the neoclassical consensus decided that inflation control is the mot important task for policy, it is no surprise that a great deal of effort has been expended upon the analysis of inflation. As such, just showing a couple time series plots is not the final word on this topic. Nevertheless, the outlook for NAIRU is not much better even if we dig deeper.The first thing to realise is that we can very easily reject the belief that NAIRU is a constant, or that inflation depends solely upon the employment gap. We need a more complex model, where other factors influence inflation, and the estimate of NAIRU changes over time (as does the CBO series).

The addition of the extra factors gives the defenders of the concept of NAIRU (and its close cousins). Those other factors always managed to shift in such a fashion so that inflation did not accelerate, even with a non-zero employment gap. So, we can find a model that has a good fit to the back history.

Unfortunately, there are two explanations for this.

- The more complex model is correct.

- The model is wrong, and the employment gap does not cause inflation to accelerate.

Neoclassical theory is highly dependent upon variables that are inferred from the data:

- the natural rate of unemployment/NAIRU;

- potential GDP (a replacement to the above);

- the natural rate of interest (r*).

Neoclassical theorists have little difficulty believing that the underlying assumptions of their theories are correct. However, outsiders have a good cause to question the falsifiability of the methodology. Since the level of the hidden variables are backed out from observed data, there is no way that historical data can deviate from the model predictions.

However, we are not interested in predicting historical events, we need forward-looking behaviour. As one might suspect, the models do a decent job in fitting economic data following smooth trends, but have a hard time dealing with turning points (mainly recessions, which is a sub-theme of my text Recessions). Longer-term extrapolations – such as inflation rising when NAIRU is hit in future years – also fail, with the failure covered up by continuous cuts to the estimated value of NAIRU.

It is safe to say that neoclassical theorists can find counter-arguments to my line of argument here. Since the objective of this text is to explain MMT, I will not pursue the argument. But from the perspective of those who are interested in how MMT fits in with financial market analysis, this is a topic that is of importance.

References and Further Reading

- Full Employment Abandoned: Shifting Sands and Policy Failures, William Mitchell and Joan Muysken, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008. ISBN: 978-1-85898-507-7

- The Case for a Job Guarantee, Pavlina R. Tcherneva, Polity Press, 2020. ISBN: 978-1-5095-4211-6

(c) Brian Romanchuk 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Posts are manually moderated, with a varying delay. Some disappear.

The comment section here is largely dead. My Substack or Twitter are better places to have a conversation.

Given that this is largely a backup way to reach me, I am going to reject posts that annoy me. Please post lengthy essays elsewhere.